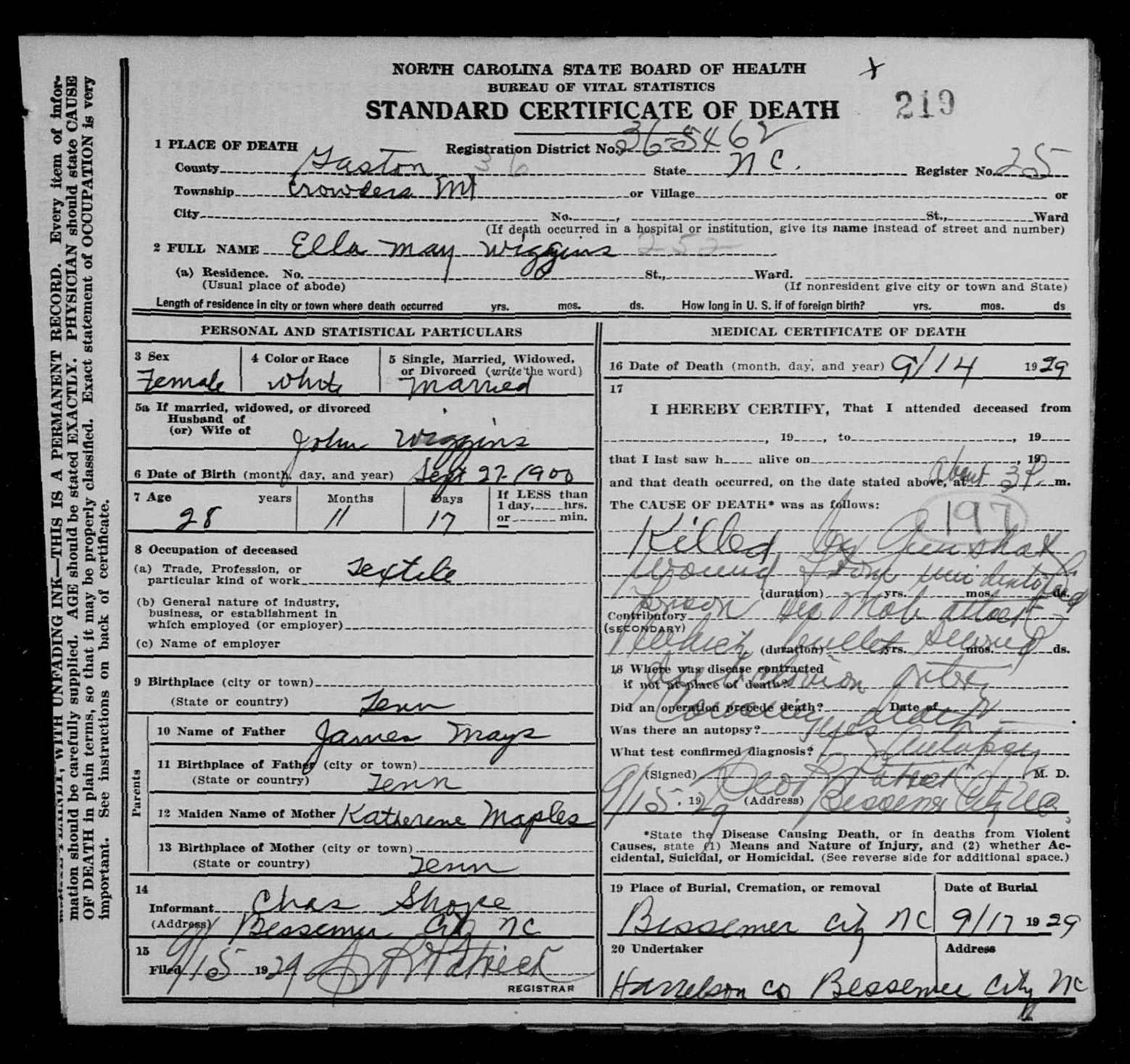

In her short twenty-nine-year life, Ella May Wiggins, a native of Sevierville, Tennessee, became a symbol of hope, activism, and the labor cause. Born September 17, 1900, she grew up in a poor family, always moving between logging camps. Her mother died when she was eighteen; her father, the following year. She married John Wiggins soon after and had a baby within a year. Her husband suggested they move to a town with a textile mill so that they would have a regular income. Their move to Cowpens, South Carolina, marked the beginning of Wiggins's difficult mill career and her first knowledge of the need for workplace reform.

The Wiggins family soon moved to another mill town, where Ella May Wiggins had seven more children, four of whom died in early childhood. During pregnancies, she continued to work in a textile mill, often on twelve-hour shifts. Around 1926 the family moved to Gaston County, North Carolina, when John Wiggins abandoned them.

It was during this time that Southern textile mill wages and working conditions were declining and worker dissatisfaction was increasing. In an effort to increase profits, mill managements throughout the region began increasing worker hours without raising wages, a practice known as a "stretch-out." Aware of these conditions, the Communist-run National Textile Workers Union (NTWU) sent Fred E. Beal, a skilled union organizer, to Charlotte. He was able to organize a small union in the Loray mill in Gastonia. In April 1929 the Loray workers began a strike, prompting workers at five other nearby mills to walk off their jobs. Soon there were about a thousand striking workers. Violence began between the strikers and city police and the police chief was killed on June 7. Sixteen unionists were charged with the killing; six were later found guilty on conspiracy to murder.

Unions and Communism were closely linked during the late 1920s, and sentiments ran high against both throughout North Carolina. In addition, local government officials and mill owners were reluctant to give up any power to a union. Despite these odds and their inherent dangers, Ella May Wiggins was an ardent unionist who had a reputation for not backing down from a fight. She learned organizational and strike tactics, became a union bookkeeper, and traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify about labor practices in the South. Her own story made her most powerful testimony: "I'm the mother of nine. Four died with the whooping cough, all at once. I was working nights, I asked the super to put me on days, so's I could tend 'em when they had their bad spells. But he wouldn't. I don't know why.…So I had to quit, and then there wasn't no money for medicine, and they just died." After she spoke, she sang powerful ballads. Her best-known song, "A Mill Mother's Lament," was sung to the tune of a 1913 ballad:

We leave our homes in the morning

We kiss our children goodbye

While we slave for the bosses

Our children scream and cry…

But understand all, workers

Our union they do fear,

Let's stand together, workers,

And have a union here.

Wiggins also tackled a task that fellow unionists had shunned: organizing African American workers. Racism was rampant in Gastonia, as elsewhere in the state and the South, in the late 1920s, but Wiggins didn't believe in segregation and knew it was important for all mill workers to unite for their cause. In one instance, Wiggins stepped over a rope separating African American and white workers at a union meeting and sat with the African Americans. In a close vote, her local NTWU branch voted to admit African Americans to the union.

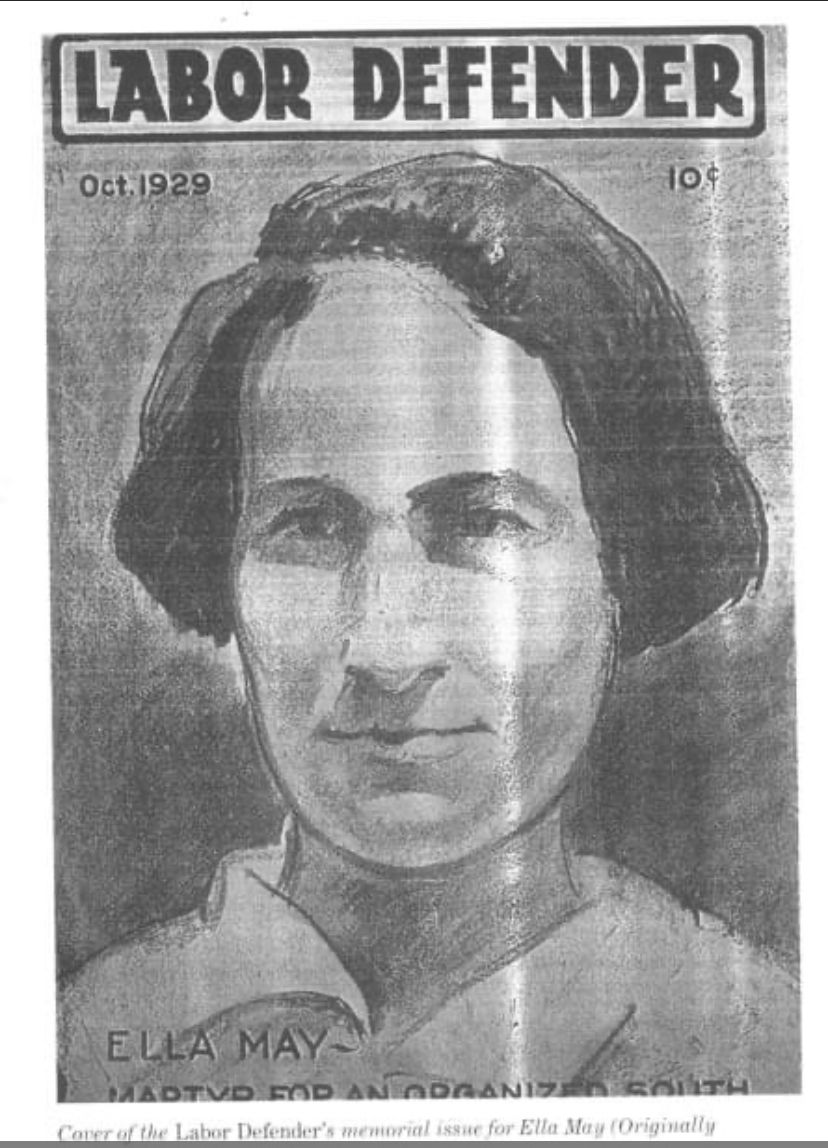

Because of her association with the NTWU and with African Americans, Wiggins was in danger from those against her causes. Receiving threats and having the water in her spring poisoned, however, did not stop Wiggins's activism. On September 14, 1929, she and other union members drove in a truck to Gastonia for a union meeting. As they arrived in town, an armed mob made them turn back. They had driven about five miles toward home when a car blocked their passage. Armed men jumped out and began shooting. Wiggins was shot in the chest and killed.

Five men were indicted for Wiggins's murder but were acquitted after less than thirty minutes of deliberation in a trial in Charlotte in March 1930. The NTWU and North Carolina mill workers, however, made sure her death was not in vain. They hailed Wiggins as a martyr for the labor reform cause and began to pressure management even harder for better working conditions, with some eventual success: the work week was eventually

In her short twenty-nine-year life, Ella May Wiggins, a native of Sevierville, Tennessee, became a symbol of hope, activism, and the labor cause. Born September 17, 1900, she grew up in a poor family, always moving between logging camps. Her mother died when she was eighteen; her father, the following year. She married John Wiggins soon after and had a baby within a year. Her husband suggested they move to a town with a textile mill so that they would have a regular income. Their move to Cowpens, South Carolina, marked the beginning of Wiggins's difficult mill career and her first knowledge of the need for workplace reform.

The Wiggins family soon moved to another mill town, where Ella May Wiggins had seven more children, four of whom died in early childhood. During pregnancies, she continued to work in a textile mill, often on twelve-hour shifts. Around 1926 the family moved to Gaston County, North Carolina, when John Wiggins abandoned them.

It was during this time that Southern textile mill wages and working conditions were declining and worker dissatisfaction was increasing. In an effort to increase profits, mill managements throughout the region began increasing worker hours without raising wages, a practice known as a "stretch-out." Aware of these conditions, the Communist-run National Textile Workers Union (NTWU) sent Fred E. Beal, a skilled union organizer, to Charlotte. He was able to organize a small union in the Loray mill in Gastonia. In April 1929 the Loray workers began a strike, prompting workers at five other nearby mills to walk off their jobs. Soon there were about a thousand striking workers. Violence began between the strikers and city police and the police chief was killed on June 7. Sixteen unionists were charged with the killing; six were later found guilty on conspiracy to murder.

Unions and Communism were closely linked during the late 1920s, and sentiments ran high against both throughout North Carolina. In addition, local government officials and mill owners were reluctant to give up any power to a union. Despite these odds and their inherent dangers, Ella May Wiggins was an ardent unionist who had a reputation for not backing down from a fight. She learned organizational and strike tactics, became a union bookkeeper, and traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify about labor practices in the South. Her own story made her most powerful testimony: "I'm the mother of nine. Four died with the whooping cough, all at once. I was working nights, I asked the super to put me on days, so's I could tend 'em when they had their bad spells. But he wouldn't. I don't know why.…So I had to quit, and then there wasn't no money for medicine, and they just died." After she spoke, she sang powerful ballads. Her best-known song, "A Mill Mother's Lament," was sung to the tune of a 1913 ballad:

We leave our homes in the morning

We kiss our children goodbye

While we slave for the bosses

Our children scream and cry…

But understand all, workers

Our union they do fear,

Let's stand together, workers,

And have a union here.

Wiggins also tackled a task that fellow unionists had shunned: organizing African American workers. Racism was rampant in Gastonia, as elsewhere in the state and the South, in the late 1920s, but Wiggins didn't believe in segregation and knew it was important for all mill workers to unite for their cause. In one instance, Wiggins stepped over a rope separating African American and white workers at a union meeting and sat with the African Americans. In a close vote, her local NTWU branch voted to admit African Americans to the union.

Because of her association with the NTWU and with African Americans, Wiggins was in danger from those against her causes. Receiving threats and having the water in her spring poisoned, however, did not stop Wiggins's activism. On September 14, 1929, she and other union members drove in a truck to Gastonia for a union meeting. As they arrived in town, an armed mob made them turn back. They had driven about five miles toward home when a car blocked their passage. Armed men jumped out and began shooting. Wiggins was shot in the chest and killed.

Five men were indicted for Wiggins's murder but were acquitted after less than thirty minutes of deliberation in a trial in Charlotte in March 1930. The NTWU and North Carolina mill workers, however, made sure her death was not in vain. They hailed Wiggins as a martyr for the labor reform cause and began to pressure management even harder for better working conditions, with some eventual success: the work week was eventually

Inscription

She Was Killed Carrying

The Torch Of Social Justice