On Saturday, Nov. 2, during the second hour of a aerobics marathon on her behalf, the third grade teacher thanked the dancers for the fund raiser. It was one of several benefits that sprang up after people in Chesterton learned that Pliske's last chance was a controversial treatment, unapproved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Pliske died Friday at the age of 42, less than a year after she learned she had breast cancer. The Chesterton native did not hold public office, but she was one of the engines that drive a community. When she fell ill, a cottage industry sprouted up to help her and her family.

"I'll never forget that courage and spirit," said Candy Davison, owner of the dance studio Creative Movement.

For more than a decade, Pliske sought pledges for aerobic marathons to help Davison raise money for the American Heart Association. Most of those years, the small town of Chesterton raised the highest total of any chapter in the country.

In Pliske's hour of need, the marathon raised $14,000. A "Pennies for Pliske" campaign at Westchester Middle School, Bailly and Chesterton High School raised more than $50,000. Tri Kappa Sorority sold pizzas.

Everyone's favorite teacher "If you had a fun fair, she was the one in the lobster suit," said LaRue Welkie, who taught third grade with Pliske for 10 years at Bailly Elementary School.

Before the cancer, Pliske's energy appeared boundless. She would rollerskate into her classroom wearing a clown wig and red nose. She stayed after class. When students weren't doing well, she showed up at their homes.

Pliske, 42, taught in the Duneland school system for 20 years, starting at Westchester Middle School followed by Jackson, Liberty and Brummitt before Bailly.

"I ran into so many people who said she was their favorite teacher," said Rogers.

The cancer Pliske was up the night of Dec. 17, working on the computer in her office at home, when she felt a twitch three times in her breast, said her husband, Ted.

Scrupulous about her health, Pliske had yearly mammograms. A year earlier, doctors had removed a benign tumor. That night, she performed a self-examination and found another lump, Ted said.

After Christmas, doctors at Michael Reese in Chicago returned a diagnosis of cancer. She had a lumpectomy and she began a regiment of chemotherapy and radiation that lasted until August. Although she felt well enough to return to class in September, she was there less than a week before she began to itch and broke out in a rash, Ted said.

After three weeks she was told the cancer had returned. At Michael Reese, the doctors took Rogers aside and told her the cancer had spread to her sister's lungs. She had less than three months to live. Rogers told Ted and they agreed not to tell Cheryl.

"I figured what was the point," Rogers said. "She would fight anyway, the way she loved life, but there didn't seem to be any reason to tell her."

Cheryl was told by their neighbor of a controversial doctor in Houston. Dr. Stanislaw Burzynski, 53, theorizes that patients with cancer lack antineoplastons in their bodies. He claims a regiment of twin chemical injections turns cancer cells into normal cells and are then flushed from the body, Ted said.

His theories have been greeted with skepticism by the medical community. The FDA has not approved the treatment, but that has not stopped Burzynski from receiving publicity. A week after Rogers enrolled her sister in the program, on Sept. 29, the TV show Hard Copy was at the Houston clinic to do a story that favored the treatment and criticized the FDA for being slow to approve the therapy, Rogers said.

"I'm not saying I'm for or against the treatment," Ted said. "I saw some people whose tumors did get smaller. But at that point there really wasn't anything else we could do."

Doctors at the clinic felt there was progress, but they stopped the treatment after Cheryl began to break out in a rash. She went home. Less than a week after appearing at the aerobic fund raiser, Cheryl was back in the clinic, which is run under the guidance of the renowned M.C. Anderson Cancer Clinic in Houston, for another round of treatment. This time she began to itch all over and the treatment was discontinued. And they went home for the last month of her life.

Time to come clean

On a sunny morning two weeks before her death, Ted sat Cheryl on the couch. Ted had met Cheryl at a junior high dance at Westchester Middle School. She was a beautiful, blonde cheerleader. One of the most popular girls in their school, he thought he never had chance. Cheryl was the only girl he had ever dated.

"I sat down in front of her and said 'Look ,we are giving it totally over to God. There is nothing we do,' " Ted said.

She had problems breathing for weeks, but she refused to believe it was because the cancer had spread to her lungs, Ted said.

Her love of life was strong until the end, Rogers said. Cheryl had already decided she did not want her life extended by machines. She died at home on Bellflower Drive at 8:25 p.m. Friday.

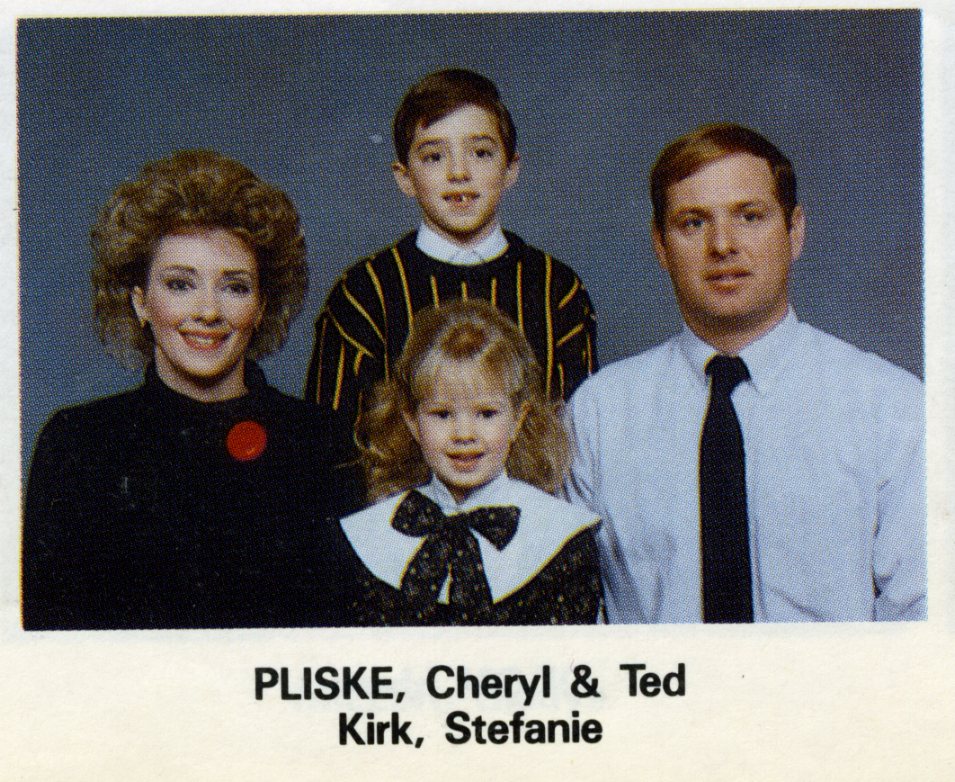

She is survived by two middle school-age children, Kirk and Stefanie. A fund set up for pay for the Burzynski treatment is still open at Indiana Federal.

Initially, Ted did not want to accept the money, but he said he will take enough to pay the medical bills. He took out a loan from his brother to pay the $12,000 the clinic wanted up front.

The rest of the money, and any other donations that come in, will be placed in a scholarship fund in his wife's name. "That would be fitting for her. She loved children. Education was her dream," Ted said.

NWI Times - December 10, 1996 - STEVE WALSH

- - -

Cheryl was the daughter of Robert D. and Jacqueline (August) Anderson. Her sister Dawn Anderson Rogers was to die from cancer in 2001 at age 46 (b 1946).

On Saturday, Nov. 2, during the second hour of a aerobics marathon on her behalf, the third grade teacher thanked the dancers for the fund raiser. It was one of several benefits that sprang up after people in Chesterton learned that Pliske's last chance was a controversial treatment, unapproved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Pliske died Friday at the age of 42, less than a year after she learned she had breast cancer. The Chesterton native did not hold public office, but she was one of the engines that drive a community. When she fell ill, a cottage industry sprouted up to help her and her family.

"I'll never forget that courage and spirit," said Candy Davison, owner of the dance studio Creative Movement.

For more than a decade, Pliske sought pledges for aerobic marathons to help Davison raise money for the American Heart Association. Most of those years, the small town of Chesterton raised the highest total of any chapter in the country.

In Pliske's hour of need, the marathon raised $14,000. A "Pennies for Pliske" campaign at Westchester Middle School, Bailly and Chesterton High School raised more than $50,000. Tri Kappa Sorority sold pizzas.

Everyone's favorite teacher "If you had a fun fair, she was the one in the lobster suit," said LaRue Welkie, who taught third grade with Pliske for 10 years at Bailly Elementary School.

Before the cancer, Pliske's energy appeared boundless. She would rollerskate into her classroom wearing a clown wig and red nose. She stayed after class. When students weren't doing well, she showed up at their homes.

Pliske, 42, taught in the Duneland school system for 20 years, starting at Westchester Middle School followed by Jackson, Liberty and Brummitt before Bailly.

"I ran into so many people who said she was their favorite teacher," said Rogers.

The cancer Pliske was up the night of Dec. 17, working on the computer in her office at home, when she felt a twitch three times in her breast, said her husband, Ted.

Scrupulous about her health, Pliske had yearly mammograms. A year earlier, doctors had removed a benign tumor. That night, she performed a self-examination and found another lump, Ted said.

After Christmas, doctors at Michael Reese in Chicago returned a diagnosis of cancer. She had a lumpectomy and she began a regiment of chemotherapy and radiation that lasted until August. Although she felt well enough to return to class in September, she was there less than a week before she began to itch and broke out in a rash, Ted said.

After three weeks she was told the cancer had returned. At Michael Reese, the doctors took Rogers aside and told her the cancer had spread to her sister's lungs. She had less than three months to live. Rogers told Ted and they agreed not to tell Cheryl.

"I figured what was the point," Rogers said. "She would fight anyway, the way she loved life, but there didn't seem to be any reason to tell her."

Cheryl was told by their neighbor of a controversial doctor in Houston. Dr. Stanislaw Burzynski, 53, theorizes that patients with cancer lack antineoplastons in their bodies. He claims a regiment of twin chemical injections turns cancer cells into normal cells and are then flushed from the body, Ted said.

His theories have been greeted with skepticism by the medical community. The FDA has not approved the treatment, but that has not stopped Burzynski from receiving publicity. A week after Rogers enrolled her sister in the program, on Sept. 29, the TV show Hard Copy was at the Houston clinic to do a story that favored the treatment and criticized the FDA for being slow to approve the therapy, Rogers said.

"I'm not saying I'm for or against the treatment," Ted said. "I saw some people whose tumors did get smaller. But at that point there really wasn't anything else we could do."

Doctors at the clinic felt there was progress, but they stopped the treatment after Cheryl began to break out in a rash. She went home. Less than a week after appearing at the aerobic fund raiser, Cheryl was back in the clinic, which is run under the guidance of the renowned M.C. Anderson Cancer Clinic in Houston, for another round of treatment. This time she began to itch all over and the treatment was discontinued. And they went home for the last month of her life.

Time to come clean

On a sunny morning two weeks before her death, Ted sat Cheryl on the couch. Ted had met Cheryl at a junior high dance at Westchester Middle School. She was a beautiful, blonde cheerleader. One of the most popular girls in their school, he thought he never had chance. Cheryl was the only girl he had ever dated.

"I sat down in front of her and said 'Look ,we are giving it totally over to God. There is nothing we do,' " Ted said.

She had problems breathing for weeks, but she refused to believe it was because the cancer had spread to her lungs, Ted said.

Her love of life was strong until the end, Rogers said. Cheryl had already decided she did not want her life extended by machines. She died at home on Bellflower Drive at 8:25 p.m. Friday.

She is survived by two middle school-age children, Kirk and Stefanie. A fund set up for pay for the Burzynski treatment is still open at Indiana Federal.

Initially, Ted did not want to accept the money, but he said he will take enough to pay the medical bills. He took out a loan from his brother to pay the $12,000 the clinic wanted up front.

The rest of the money, and any other donations that come in, will be placed in a scholarship fund in his wife's name. "That would be fitting for her. She loved children. Education was her dream," Ted said.

NWI Times - December 10, 1996 - STEVE WALSH

- - -

Cheryl was the daughter of Robert D. and Jacqueline (August) Anderson. Her sister Dawn Anderson Rogers was to die from cancer in 2001 at age 46 (b 1946).

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement