Survivor of Libby Tunnel Episode Dies

William Reynolds, Long Resident of Muskegon, Passes Away at Orlando, Fla.

Word was received in Muskegon yesterday afternoon of the death of William Reynolds, aged 84 at his home in Orlando, Fla. Funeral services were held in Orlando under the auspices of the G. A. R. in that city.

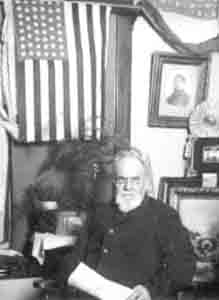

Mr. Reynolds was an old resident of Muskegon, leaving here about four years ago to make his home in Orlando, Fla. While here he was very prominent in G. A. R. circles and was justice of the peace of Muskegon for six years.

His career in the Civil war was one of the most interesting ever told by the veterans at this time. Mr. Reynolds was one of the 109 Union men who escaped from Libby prison in 1864. He spent nine months in the Confederate stronghold and worked tunnelling out for 51 days until February 9, 1864 he and his comrades made their way back to the Federal lines.

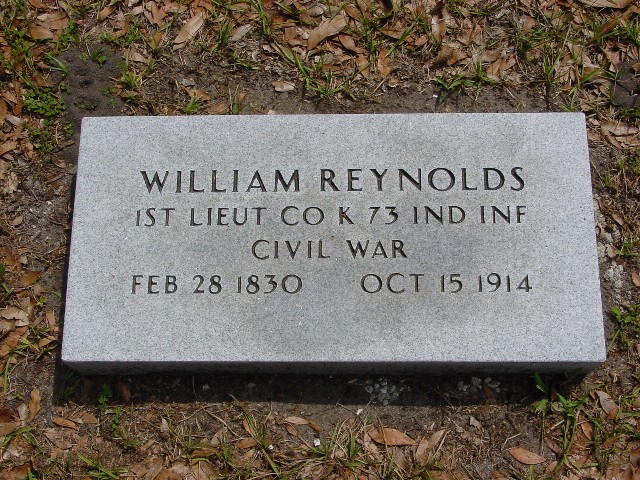

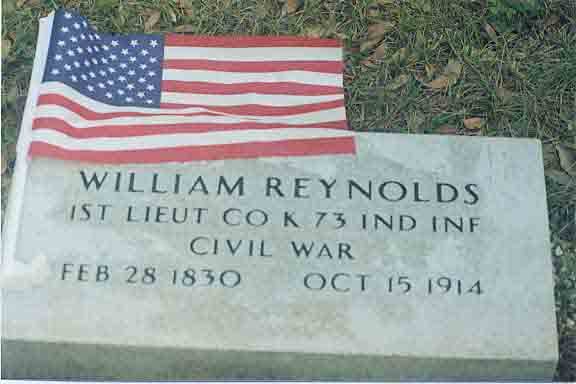

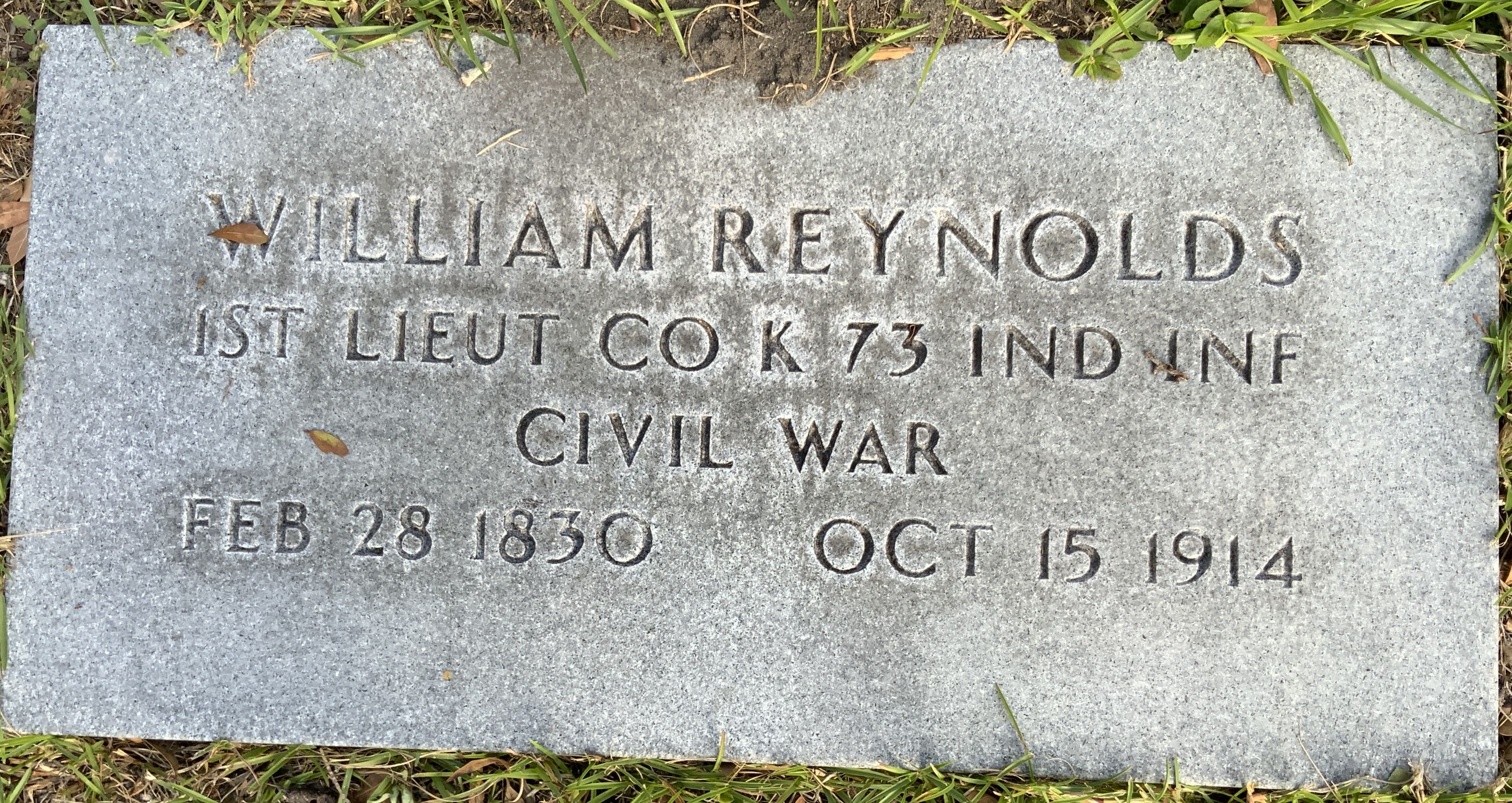

Mr. Reynolds enlisted in Company K, 73d Indiana Infantry of which company he was later made first lieutenant. After two years of service in the war he was severely wounded that he was forced to go home. Returning later and being imprisoned by the Confederates. After returning to the Federal lines following his sensational escape from Libby prison he remained at the front until the cessation of hostilities.

Mr. Reynolds was born in New York state, going to Indiana when a youth. He was the last survivor of a family of 16 and the youngest of 11 sons.

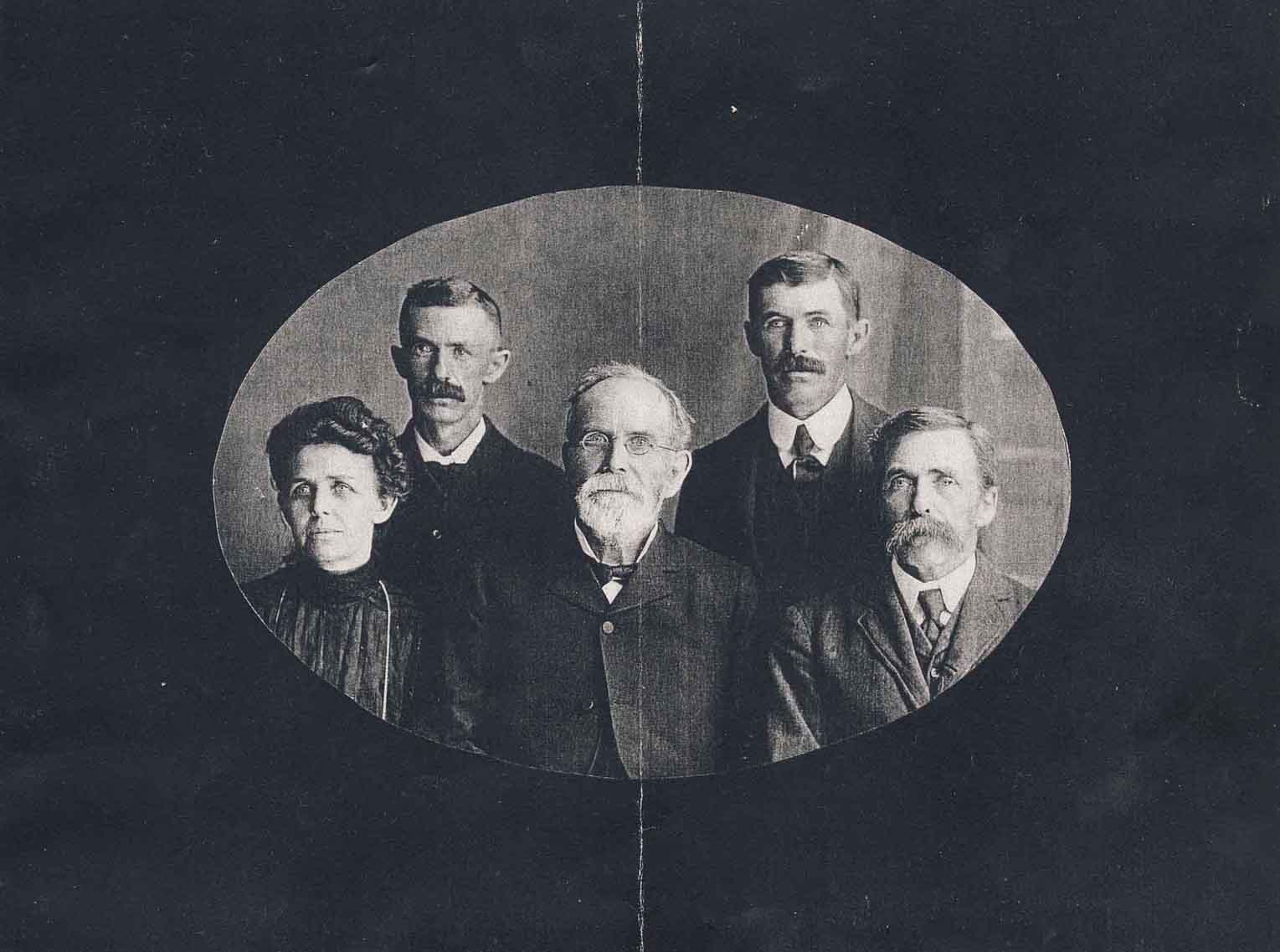

Mr. Reynolds came to Muskegon a short while after the war closed. He remained in this city until he went to Florida to make his home. In 1849 he was married in Indiana. He celebrated his golden wedding anniversary in 1899. This event was largely attended by G. A. R. members and other residents of Muskegon. His wife died about ten years ago.

In 1912, returning from Orlando, he was again married to Mrs. Mary Collins in this city. Mr. Reynolds is survived by four sons and a daughter in the west. Burt A. Gardner, a grandson, is the only living relative in Muskegon.

Muskegon Daily Chronicle, February 8, 1902

William Reynolds, one of sixteen Children, and the youngest son of eleven born to his parents, enlisted from Westville, Ind., in Co K, 73 Indiana Infantry on 10 Aug 1862. He was marching at the lead of his company to meet the enemy when he was shot in the left side of the head at the battle of Stone River, Tenn., on 31 Dec 1862, and left on the battlefield to die. He was taken prisoner and was one of the few survivors of the party of 109 union prisoners who escaped from Libby prison by means of a tunnel. For 51 nights the prisoners diligently dug the tunnel and on the night of 9 Feb 1864 they gained their freedom through one of the most sensational events of the Civil War.

William Reynolds came to Muskegon in 1880 where he engaged in building and contracting. He was also elected justice of the peace for six years and served as a notary public for thirty-one years. Reynolds retired to a fruit farm near Orlando, Florida in 1910.

Reynolds could describe graphically the digging of the infamous tunnel and his escape through eighty miles of enemy country to the nearest union line. Before he entered the tunnel he laid in a little store of rations for time of need and among his treasured keepsakes he has a little piece of beef that he saved and he says he wonders now whether it was embalmed or canned.

"Mr. Reynolds declares he knows positively that Col. Rose of the 77th Pennsylvania Infantry was the originator of the tunnel project. He was assisted in formulating the plan by Capt. Hamilton of the 12th Kentucky Cavalry and Capt. Johnson, of a New England regiment. Unfortunately, Col. Rose was recaptured after the escape.

"I was let into the scheme two or three weeks before the tunnel was completed by my second lieutenant L. P. Williams, now a resident of Washington. He had been a newspaper editor and there wasn't much going on that he didn't know. The Libby tunnel has often since the war been called "Streight's tunnel," and it has been repeatedly stated that Streight was the projector of the plan, but such is not the case. When we consider under what circumstances the Libby tunnel was dug, I think it one of the most successful engineering plots of the war and the man that first conceived the idea and then pushed it through to a successful completion, might well be proud.

"The plan was to dig through the foundation, and tunnel a distance of over sixty feet, coming out under a wood shed on the east side of the street. There was a fireplace in the partition wall between the middle and east room on the ground floor, the jambs running down into the basement below. At this time we had access to the middle or dining room as it was called. We took up the hearth from the fireplace, also the puncheon that held the dirt that the brick were laid on, thus opening an aperture sufficient for a man's body between the jambs of the chimney. All we had to do was to slip through the hold and drop to the basement below; this basement was beneath the Federal officers' hospital and was nearly filled with boxes and refuse straw from the hospital beds, etc.

"In order to keep the matter a profound secret from both the rebel authorities as well the inmates of Libby whenever anyone passed through the hole in the fireplace the hearth was immediately laid down again by one that was in the secret and the fireplace was filled with pots and kettles, and thus, day after day the prison inspector, Dick Turner, would pass through the room none the wiser of the work progressing below.

"The tunnel was commenced in Dec 1863 and finished 9 Feb 1864 at about eight or nine o'clock in the evening, when the egress was commenced. There were eighteen or twenty men engaged in digging the tunnel, but as only two or three could operate at a time, it was done by reliefs. It occupied fifty-one nights to complete the task. It might be well here to describe the tools, means of conveying dirt, etc. You may readily conclude a tunnel two feet in diameter, or nearly so, and over sixty feet long, furnished some dirt. Well, the tools were a hatchet, a two-inch chisel and a small pie pan, and the means of conveyance a wooden spittoon, two pieces of rope and an old tin pail. That constituted the outfit. The mode of operation thus: The man in the excavation with the hatchet and chisel would dig the dirt loose, (and I want you to understand that Virginia clay isn't Michigan sand, by any means, but hard and tough and full of stones), fill up the spittoon with the pie pan, and the man in the basement would by means of a rope attached to the spittoon draw it out, empty the dirt into the pail and hide it away in this refuse straw before mentioned; the man in the excavation would draw back the spittoon by means of his rope attached to the other side of the spittoon and thus the work progressed from night to night.

"The top of the excavation was about on a level with the floor of the basement and during the day it was kept covered up to prevent it's being discovered by any outside parties, but this basement was hardly ever visited by anybody----only by negro waiters.

"The work progressed without any conflicting element until two or three nights before it's completion. On the night of February 6, I think it was, the digging party thinking they had certainly gone far enough, concluded to come to the surface and explore the surroundings, so the man in the excavation made an aperture large enough to admit his head above the surface. He soon discovered that he was still in the street, but only about two feed from the aforesaid wood house; he also found that he was only a few yards from the sentinel that was traveling his beat. It so happened that the man thrust his head out just as two sentinels met, but it being quite dark, they could not discern what it was. One said to the other, "Jim, what was that?" The other remarked, "I don't know, rats, I guess; they are devilish bad about here." When the man in the tunnel found his proximity to the guard he made his head scarce in time; they then took the leg of a pair of pants, filled it with dirt and so successfully wedged it in the aperture that it was not discovered, though this was three days before the final exit.

"The reconnaissance, brief as it was, gave them the desired information; they knew just how far they had to dig. As already stated, on February 9 the grand tunnel was finished, it was arranged that the digging party should be the first to realize the benefit resulting from their labor, so about nine o'clock the digging party made their exodus.

"Next Streight bid good-bye to Libby, but came very near making a failure. The engineers of the tunnel did not take Streight's dimensions into consideration when he made his plans, and as Streight was a man that would weigh about 225 pounds he got fast in the tunnel, and for a time it was thought he would make a failure, but he finally succeeded in open air, but so weak, that for a time he was unable to stand, but finally recovered his strength. He had already made arrangements with Miss Abbie Green, a Union lady. He found his escort ready, who piloted him to a place of safety and for ten or fifteen days he was in the heart of the rebel capital and then escorted to our lines in safety.

"Most of us did not have such facilities, but some of us beat him to Washington by more than two weeks, never less. After Streight's departure the exit went quietly on but necessarily somewhat slow. They soon found out that only one could occupy the tunnel at a time on account of the want of fresh air, and to a person waiting at the mouth of the excavation for his predecessor to get through seemed an incredible long time, and his exit through sounded more like a six horse team crossing a bridge and his egress more like pulling the bung out of a tight barrel than anything I can think of.

"At about eleven o'clock the exit came to a temporary halt, and for a time we thought a general bust-up of the whole affair. It happened in this way: Two men got into a dispute over whose turn it was to go out first. [Mind you, this was in the dining room above the basement.] One declared he had done thus and so and it was his turn to go first. The other declared if he was not permitted to go first he would inform the guard and spoil the whole thing. While they were thus disputing someone ran over a kettle or something of the kind, making considerable noise. Someone else cried out to the guard, when a general stampede ensued and the whole company in waiting made for the rooms above. Col. Walker, Capt. Phelps and myself, who had been quietly waiting for a chance to pass out were standing near the foot of the stairs. The rush was so great that I was literally taken off my feet and borne to the top of the stairs by sheer force. Every man slunk away to his quarters in less time than it takes me to tell it. We expected every minute the officer of the guard would be among us demanding an explanation of the noise but in ten minutes from the time of the alarm everything was as silent as the grave excepting an occasional snore from some sleeper. We thought it very strange that the noise made in the dining room by the stampede at that time of night did not arouse the guard, but when we heard the solution it made the matter plain.

"The night before we made our exit some of the boys had sent out by the guards and bought several canteens of whiskey and had it brought in and the boys had had a huge time in this very dining room until a late hour, and the guards supposed the boys were finishing up their spree.

"Everything was perfectly quiet and as I had set my heart on getting out that night it seemed as though I must make one more trial. So I whispered to Col. Walker that I thought the way was probably clear. He told me to reconnoiter and report. I did so and found everything perfectly quiet in the dining room. I crawled back to my quarters and informed the colonel and Capt. Phelps that everything was lovely and we made one more start for freedom--this time with better success.

"When we arrived at the fireplace we found two or three, like ourselves, had made up their minds that it was about the right time to leave. We had no difficulty in passing down through the hearth to the basement below, but oh, the darkness was intense. I have often heard the remark made "as dark as a stack of black cats," but don't think I ever realized it as I did that night. We knew the excavation was almost directly across the basement from the fireplace where we entered it, so we placed out backs against the wall to get a square start, and made our way for the other side and found that we had made a bee line to the mouth of the tunnel. I will just say here that those of us who were in the secret of the escape had divided ourselves into squads of from two to four, thinking it would be safer traveling in small squads. When we arrived at the excavating I found Lieutenant Williams, [of my own company] just in the act of entering the tunnel. We bid him goodbye. Next Col. Walker entered. William stayed long enough at the other end of the tunnel to help Col. Walker out, and then he joined his squad. The man preceding would help the next man, and so on, for I tell you by the time you crawled over sixty feet in the close place you would find the tuck about all taken out of you. By the time my turn came to go out two or three more had gathered at the mouth of the excavation, and so the matter was kept up till nearly daylight and until one hundred and nine persons had passed out.

"This tunnel business was a profound secret. Some of my most intimate friends I left there, not daring to tell them, and great was the surprise of the inmates of Libby in waking up next morning to find so many of their comrades missing, but greater still was the surprise of the rebel clerk when he came up about nine o'clock next morning to get the men in line, to find their ranks so depleted.

"Late in the afternoon the rebel authorities found the mouth of the tunnel in the wood house. They sent a little darkey through and found it connected with Libby.

"I shall never forget the night when I first emerged into the open air. Just as Capt. Phelps had helped me from the tunnel the guard sang out not twenty yards from where we stood "Post No. 7 half-past one o'clock and all is well." I thought, "Old fellow, you don't know as much as you think you do."

Survivor of Libby Tunnel Episode Dies

William Reynolds, Long Resident of Muskegon, Passes Away at Orlando, Fla.

Word was received in Muskegon yesterday afternoon of the death of William Reynolds, aged 84 at his home in Orlando, Fla. Funeral services were held in Orlando under the auspices of the G. A. R. in that city.

Mr. Reynolds was an old resident of Muskegon, leaving here about four years ago to make his home in Orlando, Fla. While here he was very prominent in G. A. R. circles and was justice of the peace of Muskegon for six years.

His career in the Civil war was one of the most interesting ever told by the veterans at this time. Mr. Reynolds was one of the 109 Union men who escaped from Libby prison in 1864. He spent nine months in the Confederate stronghold and worked tunnelling out for 51 days until February 9, 1864 he and his comrades made their way back to the Federal lines.

Mr. Reynolds enlisted in Company K, 73d Indiana Infantry of which company he was later made first lieutenant. After two years of service in the war he was severely wounded that he was forced to go home. Returning later and being imprisoned by the Confederates. After returning to the Federal lines following his sensational escape from Libby prison he remained at the front until the cessation of hostilities.

Mr. Reynolds was born in New York state, going to Indiana when a youth. He was the last survivor of a family of 16 and the youngest of 11 sons.

Mr. Reynolds came to Muskegon a short while after the war closed. He remained in this city until he went to Florida to make his home. In 1849 he was married in Indiana. He celebrated his golden wedding anniversary in 1899. This event was largely attended by G. A. R. members and other residents of Muskegon. His wife died about ten years ago.

In 1912, returning from Orlando, he was again married to Mrs. Mary Collins in this city. Mr. Reynolds is survived by four sons and a daughter in the west. Burt A. Gardner, a grandson, is the only living relative in Muskegon.

Muskegon Daily Chronicle, February 8, 1902

William Reynolds, one of sixteen Children, and the youngest son of eleven born to his parents, enlisted from Westville, Ind., in Co K, 73 Indiana Infantry on 10 Aug 1862. He was marching at the lead of his company to meet the enemy when he was shot in the left side of the head at the battle of Stone River, Tenn., on 31 Dec 1862, and left on the battlefield to die. He was taken prisoner and was one of the few survivors of the party of 109 union prisoners who escaped from Libby prison by means of a tunnel. For 51 nights the prisoners diligently dug the tunnel and on the night of 9 Feb 1864 they gained their freedom through one of the most sensational events of the Civil War.

William Reynolds came to Muskegon in 1880 where he engaged in building and contracting. He was also elected justice of the peace for six years and served as a notary public for thirty-one years. Reynolds retired to a fruit farm near Orlando, Florida in 1910.

Reynolds could describe graphically the digging of the infamous tunnel and his escape through eighty miles of enemy country to the nearest union line. Before he entered the tunnel he laid in a little store of rations for time of need and among his treasured keepsakes he has a little piece of beef that he saved and he says he wonders now whether it was embalmed or canned.

"Mr. Reynolds declares he knows positively that Col. Rose of the 77th Pennsylvania Infantry was the originator of the tunnel project. He was assisted in formulating the plan by Capt. Hamilton of the 12th Kentucky Cavalry and Capt. Johnson, of a New England regiment. Unfortunately, Col. Rose was recaptured after the escape.

"I was let into the scheme two or three weeks before the tunnel was completed by my second lieutenant L. P. Williams, now a resident of Washington. He had been a newspaper editor and there wasn't much going on that he didn't know. The Libby tunnel has often since the war been called "Streight's tunnel," and it has been repeatedly stated that Streight was the projector of the plan, but such is not the case. When we consider under what circumstances the Libby tunnel was dug, I think it one of the most successful engineering plots of the war and the man that first conceived the idea and then pushed it through to a successful completion, might well be proud.

"The plan was to dig through the foundation, and tunnel a distance of over sixty feet, coming out under a wood shed on the east side of the street. There was a fireplace in the partition wall between the middle and east room on the ground floor, the jambs running down into the basement below. At this time we had access to the middle or dining room as it was called. We took up the hearth from the fireplace, also the puncheon that held the dirt that the brick were laid on, thus opening an aperture sufficient for a man's body between the jambs of the chimney. All we had to do was to slip through the hold and drop to the basement below; this basement was beneath the Federal officers' hospital and was nearly filled with boxes and refuse straw from the hospital beds, etc.

"In order to keep the matter a profound secret from both the rebel authorities as well the inmates of Libby whenever anyone passed through the hole in the fireplace the hearth was immediately laid down again by one that was in the secret and the fireplace was filled with pots and kettles, and thus, day after day the prison inspector, Dick Turner, would pass through the room none the wiser of the work progressing below.

"The tunnel was commenced in Dec 1863 and finished 9 Feb 1864 at about eight or nine o'clock in the evening, when the egress was commenced. There were eighteen or twenty men engaged in digging the tunnel, but as only two or three could operate at a time, it was done by reliefs. It occupied fifty-one nights to complete the task. It might be well here to describe the tools, means of conveying dirt, etc. You may readily conclude a tunnel two feet in diameter, or nearly so, and over sixty feet long, furnished some dirt. Well, the tools were a hatchet, a two-inch chisel and a small pie pan, and the means of conveyance a wooden spittoon, two pieces of rope and an old tin pail. That constituted the outfit. The mode of operation thus: The man in the excavation with the hatchet and chisel would dig the dirt loose, (and I want you to understand that Virginia clay isn't Michigan sand, by any means, but hard and tough and full of stones), fill up the spittoon with the pie pan, and the man in the basement would by means of a rope attached to the spittoon draw it out, empty the dirt into the pail and hide it away in this refuse straw before mentioned; the man in the excavation would draw back the spittoon by means of his rope attached to the other side of the spittoon and thus the work progressed from night to night.

"The top of the excavation was about on a level with the floor of the basement and during the day it was kept covered up to prevent it's being discovered by any outside parties, but this basement was hardly ever visited by anybody----only by negro waiters.

"The work progressed without any conflicting element until two or three nights before it's completion. On the night of February 6, I think it was, the digging party thinking they had certainly gone far enough, concluded to come to the surface and explore the surroundings, so the man in the excavation made an aperture large enough to admit his head above the surface. He soon discovered that he was still in the street, but only about two feed from the aforesaid wood house; he also found that he was only a few yards from the sentinel that was traveling his beat. It so happened that the man thrust his head out just as two sentinels met, but it being quite dark, they could not discern what it was. One said to the other, "Jim, what was that?" The other remarked, "I don't know, rats, I guess; they are devilish bad about here." When the man in the tunnel found his proximity to the guard he made his head scarce in time; they then took the leg of a pair of pants, filled it with dirt and so successfully wedged it in the aperture that it was not discovered, though this was three days before the final exit.

"The reconnaissance, brief as it was, gave them the desired information; they knew just how far they had to dig. As already stated, on February 9 the grand tunnel was finished, it was arranged that the digging party should be the first to realize the benefit resulting from their labor, so about nine o'clock the digging party made their exodus.

"Next Streight bid good-bye to Libby, but came very near making a failure. The engineers of the tunnel did not take Streight's dimensions into consideration when he made his plans, and as Streight was a man that would weigh about 225 pounds he got fast in the tunnel, and for a time it was thought he would make a failure, but he finally succeeded in open air, but so weak, that for a time he was unable to stand, but finally recovered his strength. He had already made arrangements with Miss Abbie Green, a Union lady. He found his escort ready, who piloted him to a place of safety and for ten or fifteen days he was in the heart of the rebel capital and then escorted to our lines in safety.

"Most of us did not have such facilities, but some of us beat him to Washington by more than two weeks, never less. After Streight's departure the exit went quietly on but necessarily somewhat slow. They soon found out that only one could occupy the tunnel at a time on account of the want of fresh air, and to a person waiting at the mouth of the excavation for his predecessor to get through seemed an incredible long time, and his exit through sounded more like a six horse team crossing a bridge and his egress more like pulling the bung out of a tight barrel than anything I can think of.

"At about eleven o'clock the exit came to a temporary halt, and for a time we thought a general bust-up of the whole affair. It happened in this way: Two men got into a dispute over whose turn it was to go out first. [Mind you, this was in the dining room above the basement.] One declared he had done thus and so and it was his turn to go first. The other declared if he was not permitted to go first he would inform the guard and spoil the whole thing. While they were thus disputing someone ran over a kettle or something of the kind, making considerable noise. Someone else cried out to the guard, when a general stampede ensued and the whole company in waiting made for the rooms above. Col. Walker, Capt. Phelps and myself, who had been quietly waiting for a chance to pass out were standing near the foot of the stairs. The rush was so great that I was literally taken off my feet and borne to the top of the stairs by sheer force. Every man slunk away to his quarters in less time than it takes me to tell it. We expected every minute the officer of the guard would be among us demanding an explanation of the noise but in ten minutes from the time of the alarm everything was as silent as the grave excepting an occasional snore from some sleeper. We thought it very strange that the noise made in the dining room by the stampede at that time of night did not arouse the guard, but when we heard the solution it made the matter plain.

"The night before we made our exit some of the boys had sent out by the guards and bought several canteens of whiskey and had it brought in and the boys had had a huge time in this very dining room until a late hour, and the guards supposed the boys were finishing up their spree.

"Everything was perfectly quiet and as I had set my heart on getting out that night it seemed as though I must make one more trial. So I whispered to Col. Walker that I thought the way was probably clear. He told me to reconnoiter and report. I did so and found everything perfectly quiet in the dining room. I crawled back to my quarters and informed the colonel and Capt. Phelps that everything was lovely and we made one more start for freedom--this time with better success.

"When we arrived at the fireplace we found two or three, like ourselves, had made up their minds that it was about the right time to leave. We had no difficulty in passing down through the hearth to the basement below, but oh, the darkness was intense. I have often heard the remark made "as dark as a stack of black cats," but don't think I ever realized it as I did that night. We knew the excavation was almost directly across the basement from the fireplace where we entered it, so we placed out backs against the wall to get a square start, and made our way for the other side and found that we had made a bee line to the mouth of the tunnel. I will just say here that those of us who were in the secret of the escape had divided ourselves into squads of from two to four, thinking it would be safer traveling in small squads. When we arrived at the excavating I found Lieutenant Williams, [of my own company] just in the act of entering the tunnel. We bid him goodbye. Next Col. Walker entered. William stayed long enough at the other end of the tunnel to help Col. Walker out, and then he joined his squad. The man preceding would help the next man, and so on, for I tell you by the time you crawled over sixty feet in the close place you would find the tuck about all taken out of you. By the time my turn came to go out two or three more had gathered at the mouth of the excavation, and so the matter was kept up till nearly daylight and until one hundred and nine persons had passed out.

"This tunnel business was a profound secret. Some of my most intimate friends I left there, not daring to tell them, and great was the surprise of the inmates of Libby in waking up next morning to find so many of their comrades missing, but greater still was the surprise of the rebel clerk when he came up about nine o'clock next morning to get the men in line, to find their ranks so depleted.

"Late in the afternoon the rebel authorities found the mouth of the tunnel in the wood house. They sent a little darkey through and found it connected with Libby.

"I shall never forget the night when I first emerged into the open air. Just as Capt. Phelps had helped me from the tunnel the guard sang out not twenty yards from where we stood "Post No. 7 half-past one o'clock and all is well." I thought, "Old fellow, you don't know as much as you think you do."

Family Members

-

![]()

Daniel Reynolds

1805–1890

-

![]()

Elizabeth "Lizzie" Reynolds Hester Goodnough

1807–1888

-

![]()

Phebe Reynolds Raines Charles

1809–1896

-

Josiah Reynolds

1810 – unknown

-

![]()

David Reynolds

1811–1879

-

![]()

Reuben Reynolds

1813–1896

-

Stephen Reynolds

1814 – unknown

-

![]()

Hannah Reynolds Hester

1816–1857

-

![]()

Sarah Reynolds Burgess

1817–1905

-

![]()

Benjamin Cornell Reynolds

1819–1916

-

![]()

Amos B Reynolds

1821–1891

-

![]()

Anna Reynolds Huddleston

1823–1905

-

Jonathan Reynolds

1824–1829

-

![]()

Silas Hyatt Reynolds

1826–1909

-

![]()

Nathan Reynolds

1828–1829

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement