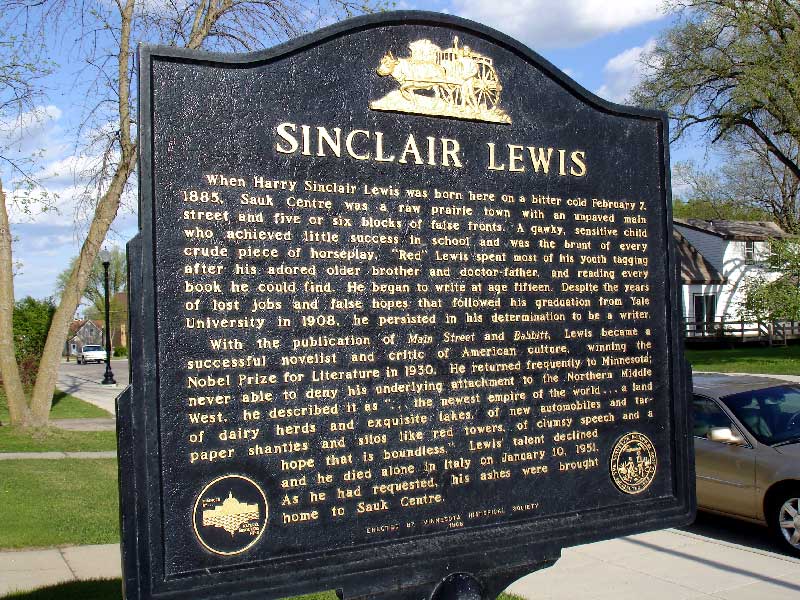

With some 1,200 people, Sauk Centre-in the central part of Minnesota, about one hundred miles northwest of Minneapolis-seemed more lucrative than the isolated village of Ironton. Lewis's wife, Emma, was reluctant to make the move, for the new town was barren of trees and grass and flowers, a raw western village of false-fronted stores along a dusty, unpaved Main Street.

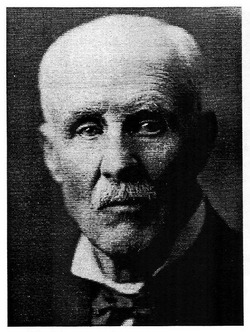

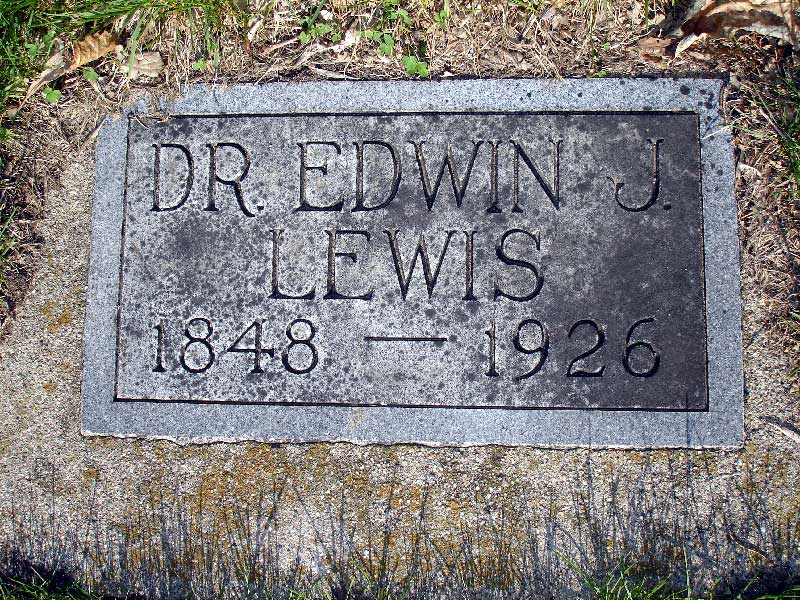

None of Dr. Lewis's Yankee forebears were physicians. His mother Emeline's family was descended from Peregrine White, the first English child born in the New World. His father, John Lewis, started out as a farmer in Westville, Connecticut, but in 1848 contracted a case of the gold itch and signed on with a company of New Haven men who chartered a ship and made the long voyage around the Horn to California. The venture was a failure, and John returned to his wife and new son, Edwin J., the fifth of six children, born not long before he had gone west.

Like many New England farmers whose land was depleted, John Lewis sold out and headed west. He and his family got as far as Lisburn in south-central Pennsylvania, where he founded a match factory. Edwin finished school there and became a teacher. In 1866, the family moved to Minnesota, and homesteaded a quarter section near the village of Elysian, in the southern part of the state. This is drab, hilly country, splotched with forests, glacial lakes, marshes, and clay pits. But there was rich soil, and John succeeded as a farmer, owning the best yoke of oxen in the area.

Edwin continued training scholars in a one-room school near Elysian. A contemporary sized him up as "a handsome quick-witted young athlete ready to fight at the drop of the Hat and just as ready to shake and make up." At Elysian, he fell in love with a slim, red-haired teacher named Emma Kermott. She left few traces in history. Her brother described her as so serious-minded that she "couldn't see a joke till it was told forward & backward." But she was "passionately devoted to her family" and never said "an ill word about any human being." Edwin and Emma were married on December 28, 1873, in Waseca, the nearest county seat.

Emma's father, Edward Payson Kermott, had died only the previous year. He was a homeopathic physician; two of his brothers were regular doctors. In the late 1850s, he had immigrated to Minnesota from London, Ontario. (The family came originally from the Isle of Man in England.) He had had tuberculosis and had perhaps been lured to the territory by land boomers' propaganda that the air was salubrious. TB is not a hereditary ailment; however, it later killed his daughter.

Edward Kermott lived in a string of Minnesota towns; his son Edward called him a "rolling stone." He served as a corporal in the Union Army for a year and returned to Minnesota to practice homeopathy and perform dentistry as a sideline. He also farmed and was elected justice of the peace. One of his trials was locally notorious. Justice Kermott appeared well-lubricated with frontier corn liquor supplied by the defendant. The plaintiff protested a ruling by grabbing Kermott's beard and dragging him under the table. From this vantage point the judge tipsily yelled, "I fine you five dollars for contempt of court!"

This snapshot of Dr. Kermott for posterity may be a caricature, but it brings up a possible hereditary link to his grandson, and also a great-grandson and two great granddaughters: alcoholism. Sinclair Lewis was an alcoholic; his brothers Claude and Fred were not. There is no doubt that Dr. Kermott passed on another trait: his red hair. His daughter and all her sons but Fred had it.

The direct inspiration for Ed Lewis becoming a doctor was not his father-in-law but an Elysian physician named Flynn, who let him "read medicine." But with a wife and a child-Fred was born in 1875-Ed took a job teaching in Red Wing, more than sixty miles away. With money borrowed from Emma's brother, he entered Rush Medical College in Chicago. Emma and Fred stayed with his parents while he boarded with the Warner family in suburban Wilmette.

The move from Ironton to Sauk Centre considerably boosted the young doctor's income. His second son, Claude, was born in 1878, and on February 7, 1885, his third and youngest son, Harry Sinclair Lewis. (Sinclair was the surname of a dentist friend.) Four years later, Dr. E.J. (as he was known to family and friends) was doing well enough to purchase for $2,800 a ten-room house at 812 Third Street, directly across the street from Harry's birthplace. It was a generic frame house common to Midwestern small towns. In the back of the parlor and family room, the doctor consulted patients after office hours. There was also a small barn on the back alley bordering the yard. A stairway in the hall led up to the second floor, which contained a master bedroom, a guest room, the boys' bedroom, and a maid's garret.

Dr. E.J. made country calls four or five times a week. On fierce winter nights, with temperatures down to thirty below, bundled in fur rugs and a coonskin coat, he drove a sleigh across trackless snowy fields, taking his bearings on a distant Catholic church steeple, then delivered a baby in a bedroom or performed surgery on a kitchen table by lamplight. A county history describes him as a "typical and able family physician." Dr. Lewis's account books reveal a man who kept track of every bill owed him, but he eventually wrote off unpaid debts, inscribing a dry "dead beat" or "left county" beside their names.

The account books are the only autobiography he left, a meticulous ledger of money incoming and outgoing. He recorded minute daily household expenditures-meat, flour, ice, coal, oysters, church tithes, cigars, clothing, cords of wood. In 1907, this notation appears: "Collected in last 20 years $65,473 or an average of $3273.00 cash for year." At his peak, he netted $1,000 a year-a comfortable living. He paid off the mortgage on his parents' property and later invested in mortgages on North Dakota farmland, which earned him a steady 6 percent-like Cascarets, he liked to say, referring to a patent laxative with the slogan "works while you sleep."

From that analogy, a Freudian might diagnose an anal fixation, but Dr. E.J. was no miser. He worked hard, lived well, sent his boys to college, supported a well-dressed wife who ordered her clothes from Marshall Field, and took a month off every summer to attend the annual meeting of the American Medical Association and make longer jaunts to places such as Denver, Yellowstone Park, and California. Opening day of the hunting season found him with a dog trudging the brown-stubbled fields around Sauk Centre, banging away at prairie chickens. He once bagged eight birds in eight consecutive shots. Beyond making enough to meet his obligations and cushion his old age, he told Harry he wanted "to lay aside a thousand or two 'plunks' for you boys 'to blow' when we get through, if any is left."

In manner, he was "very dignified, stern, rather soldierly, absolutely honest." His neighbors considered him somewhat aloof, though congenial with a few close friends. The doctor had that quintessential New England-Puritan virtue: "steady habits." Literally. Sauk Centre people joked they could set their watches by his morning walk to the office, precisely at 7:00, to light the stove, then home for breakfast; back to the office, home for lunch at 12:00, dinner at precisely 6:00.

He was true to his heritage in valuing hard work, frugality, practicality, and taciturnity. He did not express his feelings, preferring laconic irony. As a doctor, he had observed enough human frailties to regard sinners with bemused tolerance. He attended the Congregational Church regularly but not religiously; busybodies left him cold. Thus, he wrote his son that the Methodist pastor "is poking his nose into everything and keeps the people quite well stirred up to the amusement of the old hoary headed sinners." He directed shafts of wry humor at folks with airs and at medical competitors. Of one of the latter he said, "If he only had brains to back up his assurance,

J. Pierpont Morgan would not be in it with him."

He sometimes regretted being only a country doctor. Had he not had a family to support, "I might have been a John B. Murphy," he told Harry, referring to a Rush classmate who became a prominent Chicago surgeon. He was to achieve his ambition vicariously through his middle son, Claude, a husky, stocky lad, strong swimmer, ice-skater, football player, hunter, good student, truant, and prankster. (One Halloween, he and some pals moved outhouses from all over town to behind the church; another time, they put frogs in a baptismal font.) He graduated from the state U, then from Rush; he trained as a surgeon in Chicago before moving to Saint Cloud, where he practiced as a surgeon and had his own clinic. Fred was sent to dental school at Columbia University in New York City but dropped out after eight months. He came home and later married Vendala Hanson, known as Winnie, a Swedish farmer's daughter. Gossip at the time had it that the groom's family disapproved of her as lower class. Harry wrote about the wedding in his diary and-foretelling the future-sided with the Swedes, whom he describes as "high-class Scandinavians" and "ladies and gentlemen." Fred tried farming, then worked for, and for a time ran, a local flour mill. If Fred had stuck with dentistry, Dr. E.J. said, he could have been making three thousand plunks a year, but unlike Claude and Harry he lacked ambition; still, he was "probably happier than any of the rest of us."

As for Harry, there is a story that Dr. E.J. once said to Fred and Claude: "You boys will always be able to make a living. But poor Harry, there's nothing he can do."

Emma Kermott Lewis fell ill of tuberculosis when Harry was three, and Dr. E.J. placed her in a sanatorium in Arizona the following winter. The climate seemed to help her condition, and she returned to Sauk Centre for the summer. But the following winter her condition worsened, and from then on her decline was inexorable. The doctor-father, fearful of contagion, would have kept the child from her room. There was the whispered conspiracy of the sickroom, the worried adult faces, the palpable sense of something dark and terrifying about to happen. Then, in the words of the Sauk Centre Avalanche:

On Thursday last, June 25, after a noble struggle for life, the spirit of Mrs. E. J. Lewis took its flight, and the gloom and desolation attendant settled over a happy household. . . . Her family, consisting of her husband and three boys aged 15, 13 and 6 years, are deeply afflicted.

Emma had been an important presence in Sinclair Lewis's infancy, and in death she became an important absence in his life. An inner void opened up where once was her tenderness. He later said he could not remember her, but in his subconscious lurked a lost child-

alternately withdrawn and hostile. His sixth-grade teacher, Evelyn Pribble, left a glimpse of him as "somehow not alive to the world around himself. . . . He didn't apply himself to his school work and seemed to be indifferent about his grades," which were near the bottom of the class.

Friends urged Dr. E.J. to get the boys a mother. A little over a year after Emma died, on July 7, 1892, he married Isabel Warner, daughter of the family in Wilmette with whom he had boarded while in medical school. It may have been more marriage of convenience and friendship than love match, but the doctor was a practical man. Isabel was a plain, pleasant-faced, kindly woman, not flattered by the camera; in pictures, she vaguely resembles Queen Victoria, an unsmiling woman in voluminous dresses. A schoolmate of Harry's described her as "rather reticent and quiet" and "motherly." Psychologically, Sinclair Lewis later wrote, she was "more mother than stepmother" and "psychically my own mother." But while he called her "Mother" or "Ma," when he was angry at her he referred to her as his stepmother, as though withdrawing her legitimacy. It would seem he had a dual mother: the real Isabel, dealing with matters of education and discipline, and, behind her, the faint aura of his real mother, a lingering memory of ineffable tenderness, mingled with terrible loss.

The forty-year-old bride Dr. E.J. brought to Sauk Centre took a big step by moving to a small prairie town from suburban Wilmette and surely had some misgivings. As the doctor's wife, she inherited an important status in town society, and she set about quietly to consolidate it. She became a pillar of the cultural Gradatim Club, a bulwark of the Monday Musical Club (she played the piano), and a rock of the Order of the Eastern Star. She was always in the forefront of the latest beautification projects-planting trees along Sauk Lake and creating a park to replace the polluted site left by the defunct brewery; distributing packets of flower seeds for spring gardens. Her crowning good work was Sauk Centre's rest room for farm wives and their children, said to be one of the first in the nation. It answered a real need for a place where wives could take their children and relax while their husbands did business or drank in the saloons.

Harry became something of a mama's boy and listened in on the Gradatim Club ladies in the Lewis parlor. Out of overprotection, Isabel took him along with her on trips. She dressed him well and taught him good manners; boys who had much less to spend and fewer fancy clothes regarded him as different in that way.

"Harry was always different," said Ben DuBois, son of Dr. Julian DuBois, physician and civil leader. Reviewing a novel years later, Sinclair Lewis made indirect answer as he spoke of the main character but really of himself: "If the reader was himself a rather stodgy child, he here finds faithfully set down what it was that the dreamy child whom he could never understand and thought 'queer' or 'old-fashioned' was thinking." "He had this terrific imagination and kids are realists, y'know," DuBois told reporters in later years, when he was the town's leading banker. He "didn't ever own a watch," meaning he didn't know the time of day.

Copyright 2002 by Richard Lingeman

With some 1,200 people, Sauk Centre-in the central part of Minnesota, about one hundred miles northwest of Minneapolis-seemed more lucrative than the isolated village of Ironton. Lewis's wife, Emma, was reluctant to make the move, for the new town was barren of trees and grass and flowers, a raw western village of false-fronted stores along a dusty, unpaved Main Street.

None of Dr. Lewis's Yankee forebears were physicians. His mother Emeline's family was descended from Peregrine White, the first English child born in the New World. His father, John Lewis, started out as a farmer in Westville, Connecticut, but in 1848 contracted a case of the gold itch and signed on with a company of New Haven men who chartered a ship and made the long voyage around the Horn to California. The venture was a failure, and John returned to his wife and new son, Edwin J., the fifth of six children, born not long before he had gone west.

Like many New England farmers whose land was depleted, John Lewis sold out and headed west. He and his family got as far as Lisburn in south-central Pennsylvania, where he founded a match factory. Edwin finished school there and became a teacher. In 1866, the family moved to Minnesota, and homesteaded a quarter section near the village of Elysian, in the southern part of the state. This is drab, hilly country, splotched with forests, glacial lakes, marshes, and clay pits. But there was rich soil, and John succeeded as a farmer, owning the best yoke of oxen in the area.

Edwin continued training scholars in a one-room school near Elysian. A contemporary sized him up as "a handsome quick-witted young athlete ready to fight at the drop of the Hat and just as ready to shake and make up." At Elysian, he fell in love with a slim, red-haired teacher named Emma Kermott. She left few traces in history. Her brother described her as so serious-minded that she "couldn't see a joke till it was told forward & backward." But she was "passionately devoted to her family" and never said "an ill word about any human being." Edwin and Emma were married on December 28, 1873, in Waseca, the nearest county seat.

Emma's father, Edward Payson Kermott, had died only the previous year. He was a homeopathic physician; two of his brothers were regular doctors. In the late 1850s, he had immigrated to Minnesota from London, Ontario. (The family came originally from the Isle of Man in England.) He had had tuberculosis and had perhaps been lured to the territory by land boomers' propaganda that the air was salubrious. TB is not a hereditary ailment; however, it later killed his daughter.

Edward Kermott lived in a string of Minnesota towns; his son Edward called him a "rolling stone." He served as a corporal in the Union Army for a year and returned to Minnesota to practice homeopathy and perform dentistry as a sideline. He also farmed and was elected justice of the peace. One of his trials was locally notorious. Justice Kermott appeared well-lubricated with frontier corn liquor supplied by the defendant. The plaintiff protested a ruling by grabbing Kermott's beard and dragging him under the table. From this vantage point the judge tipsily yelled, "I fine you five dollars for contempt of court!"

This snapshot of Dr. Kermott for posterity may be a caricature, but it brings up a possible hereditary link to his grandson, and also a great-grandson and two great granddaughters: alcoholism. Sinclair Lewis was an alcoholic; his brothers Claude and Fred were not. There is no doubt that Dr. Kermott passed on another trait: his red hair. His daughter and all her sons but Fred had it.

The direct inspiration for Ed Lewis becoming a doctor was not his father-in-law but an Elysian physician named Flynn, who let him "read medicine." But with a wife and a child-Fred was born in 1875-Ed took a job teaching in Red Wing, more than sixty miles away. With money borrowed from Emma's brother, he entered Rush Medical College in Chicago. Emma and Fred stayed with his parents while he boarded with the Warner family in suburban Wilmette.

The move from Ironton to Sauk Centre considerably boosted the young doctor's income. His second son, Claude, was born in 1878, and on February 7, 1885, his third and youngest son, Harry Sinclair Lewis. (Sinclair was the surname of a dentist friend.) Four years later, Dr. E.J. (as he was known to family and friends) was doing well enough to purchase for $2,800 a ten-room house at 812 Third Street, directly across the street from Harry's birthplace. It was a generic frame house common to Midwestern small towns. In the back of the parlor and family room, the doctor consulted patients after office hours. There was also a small barn on the back alley bordering the yard. A stairway in the hall led up to the second floor, which contained a master bedroom, a guest room, the boys' bedroom, and a maid's garret.

Dr. E.J. made country calls four or five times a week. On fierce winter nights, with temperatures down to thirty below, bundled in fur rugs and a coonskin coat, he drove a sleigh across trackless snowy fields, taking his bearings on a distant Catholic church steeple, then delivered a baby in a bedroom or performed surgery on a kitchen table by lamplight. A county history describes him as a "typical and able family physician." Dr. Lewis's account books reveal a man who kept track of every bill owed him, but he eventually wrote off unpaid debts, inscribing a dry "dead beat" or "left county" beside their names.

The account books are the only autobiography he left, a meticulous ledger of money incoming and outgoing. He recorded minute daily household expenditures-meat, flour, ice, coal, oysters, church tithes, cigars, clothing, cords of wood. In 1907, this notation appears: "Collected in last 20 years $65,473 or an average of $3273.00 cash for year." At his peak, he netted $1,000 a year-a comfortable living. He paid off the mortgage on his parents' property and later invested in mortgages on North Dakota farmland, which earned him a steady 6 percent-like Cascarets, he liked to say, referring to a patent laxative with the slogan "works while you sleep."

From that analogy, a Freudian might diagnose an anal fixation, but Dr. E.J. was no miser. He worked hard, lived well, sent his boys to college, supported a well-dressed wife who ordered her clothes from Marshall Field, and took a month off every summer to attend the annual meeting of the American Medical Association and make longer jaunts to places such as Denver, Yellowstone Park, and California. Opening day of the hunting season found him with a dog trudging the brown-stubbled fields around Sauk Centre, banging away at prairie chickens. He once bagged eight birds in eight consecutive shots. Beyond making enough to meet his obligations and cushion his old age, he told Harry he wanted "to lay aside a thousand or two 'plunks' for you boys 'to blow' when we get through, if any is left."

In manner, he was "very dignified, stern, rather soldierly, absolutely honest." His neighbors considered him somewhat aloof, though congenial with a few close friends. The doctor had that quintessential New England-Puritan virtue: "steady habits." Literally. Sauk Centre people joked they could set their watches by his morning walk to the office, precisely at 7:00, to light the stove, then home for breakfast; back to the office, home for lunch at 12:00, dinner at precisely 6:00.

He was true to his heritage in valuing hard work, frugality, practicality, and taciturnity. He did not express his feelings, preferring laconic irony. As a doctor, he had observed enough human frailties to regard sinners with bemused tolerance. He attended the Congregational Church regularly but not religiously; busybodies left him cold. Thus, he wrote his son that the Methodist pastor "is poking his nose into everything and keeps the people quite well stirred up to the amusement of the old hoary headed sinners." He directed shafts of wry humor at folks with airs and at medical competitors. Of one of the latter he said, "If he only had brains to back up his assurance,

J. Pierpont Morgan would not be in it with him."

He sometimes regretted being only a country doctor. Had he not had a family to support, "I might have been a John B. Murphy," he told Harry, referring to a Rush classmate who became a prominent Chicago surgeon. He was to achieve his ambition vicariously through his middle son, Claude, a husky, stocky lad, strong swimmer, ice-skater, football player, hunter, good student, truant, and prankster. (One Halloween, he and some pals moved outhouses from all over town to behind the church; another time, they put frogs in a baptismal font.) He graduated from the state U, then from Rush; he trained as a surgeon in Chicago before moving to Saint Cloud, where he practiced as a surgeon and had his own clinic. Fred was sent to dental school at Columbia University in New York City but dropped out after eight months. He came home and later married Vendala Hanson, known as Winnie, a Swedish farmer's daughter. Gossip at the time had it that the groom's family disapproved of her as lower class. Harry wrote about the wedding in his diary and-foretelling the future-sided with the Swedes, whom he describes as "high-class Scandinavians" and "ladies and gentlemen." Fred tried farming, then worked for, and for a time ran, a local flour mill. If Fred had stuck with dentistry, Dr. E.J. said, he could have been making three thousand plunks a year, but unlike Claude and Harry he lacked ambition; still, he was "probably happier than any of the rest of us."

As for Harry, there is a story that Dr. E.J. once said to Fred and Claude: "You boys will always be able to make a living. But poor Harry, there's nothing he can do."

Emma Kermott Lewis fell ill of tuberculosis when Harry was three, and Dr. E.J. placed her in a sanatorium in Arizona the following winter. The climate seemed to help her condition, and she returned to Sauk Centre for the summer. But the following winter her condition worsened, and from then on her decline was inexorable. The doctor-father, fearful of contagion, would have kept the child from her room. There was the whispered conspiracy of the sickroom, the worried adult faces, the palpable sense of something dark and terrifying about to happen. Then, in the words of the Sauk Centre Avalanche:

On Thursday last, June 25, after a noble struggle for life, the spirit of Mrs. E. J. Lewis took its flight, and the gloom and desolation attendant settled over a happy household. . . . Her family, consisting of her husband and three boys aged 15, 13 and 6 years, are deeply afflicted.

Emma had been an important presence in Sinclair Lewis's infancy, and in death she became an important absence in his life. An inner void opened up where once was her tenderness. He later said he could not remember her, but in his subconscious lurked a lost child-

alternately withdrawn and hostile. His sixth-grade teacher, Evelyn Pribble, left a glimpse of him as "somehow not alive to the world around himself. . . . He didn't apply himself to his school work and seemed to be indifferent about his grades," which were near the bottom of the class.

Friends urged Dr. E.J. to get the boys a mother. A little over a year after Emma died, on July 7, 1892, he married Isabel Warner, daughter of the family in Wilmette with whom he had boarded while in medical school. It may have been more marriage of convenience and friendship than love match, but the doctor was a practical man. Isabel was a plain, pleasant-faced, kindly woman, not flattered by the camera; in pictures, she vaguely resembles Queen Victoria, an unsmiling woman in voluminous dresses. A schoolmate of Harry's described her as "rather reticent and quiet" and "motherly." Psychologically, Sinclair Lewis later wrote, she was "more mother than stepmother" and "psychically my own mother." But while he called her "Mother" or "Ma," when he was angry at her he referred to her as his stepmother, as though withdrawing her legitimacy. It would seem he had a dual mother: the real Isabel, dealing with matters of education and discipline, and, behind her, the faint aura of his real mother, a lingering memory of ineffable tenderness, mingled with terrible loss.

The forty-year-old bride Dr. E.J. brought to Sauk Centre took a big step by moving to a small prairie town from suburban Wilmette and surely had some misgivings. As the doctor's wife, she inherited an important status in town society, and she set about quietly to consolidate it. She became a pillar of the cultural Gradatim Club, a bulwark of the Monday Musical Club (she played the piano), and a rock of the Order of the Eastern Star. She was always in the forefront of the latest beautification projects-planting trees along Sauk Lake and creating a park to replace the polluted site left by the defunct brewery; distributing packets of flower seeds for spring gardens. Her crowning good work was Sauk Centre's rest room for farm wives and their children, said to be one of the first in the nation. It answered a real need for a place where wives could take their children and relax while their husbands did business or drank in the saloons.

Harry became something of a mama's boy and listened in on the Gradatim Club ladies in the Lewis parlor. Out of overprotection, Isabel took him along with her on trips. She dressed him well and taught him good manners; boys who had much less to spend and fewer fancy clothes regarded him as different in that way.

"Harry was always different," said Ben DuBois, son of Dr. Julian DuBois, physician and civil leader. Reviewing a novel years later, Sinclair Lewis made indirect answer as he spoke of the main character but really of himself: "If the reader was himself a rather stodgy child, he here finds faithfully set down what it was that the dreamy child whom he could never understand and thought 'queer' or 'old-fashioned' was thinking." "He had this terrific imagination and kids are realists, y'know," DuBois told reporters in later years, when he was the town's leading banker. He "didn't ever own a watch," meaning he didn't know the time of day.

Copyright 2002 by Richard Lingeman

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement